“What does it mean to be a paqo?” “Is it okay to call ourselves paqos?” These are common questions asked by people  interested in the Andean sacred arts or who are studying the tradition. They are curious about the different kinds of paqos, how paqos go about their daily lives, what their responsibilities are, and the like. In this post I have gathered together many of these questions and provided my answers to them. The information I provide is my own understanding and knowledge of this tradition, and so nothing I share should be taken as anything more than my opinion.

interested in the Andean sacred arts or who are studying the tradition. They are curious about the different kinds of paqos, how paqos go about their daily lives, what their responsibilities are, and the like. In this post I have gathered together many of these questions and provided my answers to them. The information I provide is my own understanding and knowledge of this tradition, and so nothing I share should be taken as anything more than my opinion.

Question: There are two levels of paqos: pampa mesayoqs and alto mesayoqs. What are the differences?

Pampa mesayoq and alto mesayoq are not designations of “levels,” but simply different kinds of paqos. They practice in similar ways, with a few distinct differences that characterize them as two different types of paqos. Pampa mesayoq can be translated, or understood to mean, the keeper of the earth signs or low signs. Alto mesayoq means keeper of the high signs. Both kinds of paqos share common knowledge, such as of making and offering haywarisqas (despachos), carrying a misha (mesa), healing, and so on. The main difference is that, according to the “old ways,” an alto mesayoq has mystical capacities that a pampa mesayoq does not. For example, alto mesayoqs can “talk” directly to spirit beings, such as an apu (mountain spirit), whereas a pampa mesayoq can only communicate with the spirits indirectly, such as through their misha or dreams. I don’t know if this distinction holds true today, but according to my teacher don Juan Nuñez del Prado, this has always been the main distinction between the two types of paqos.

That said, there is a specific way to think about paqos—both pampa mesayoqs and alto mesayoqs—as having “levels,” because there are stages to their development as paqos. These stages correlate to their accessing and being able to use more personal power. The levels, which are most commonly applied to alto mesayoqs, are: ayllu alto mesayoq, llaqta alto mesayoq, and suyu alto mesayoq. Usually paqos are “in service” to an apu, which is their guiding spirit. The apu teaches them and so helps them develop. All paqos start out in service to an ayllu apu, or an apu whose range of power is limited, such as to a village or town, or a small cluster of them. Hence, they are known as ayllu alto mesayoqs. As they develop their abilities, they may eventually be called by a more powerful apu, usually a llaqta apu, whose range of power reaches wider and farther, encompassing a larger region. Those paqos have reached a stage of development so that their power is equivalent to that of the apu, and so the paqo is recognized as a llaqta alto mesayoq. As paqos continue to learn and grow, they may be called by the greatest of apus, a suyu apu, whose power reaches across a vast region or even an entire nation. Once in service to this highest level of apu, these paqos are recognized as suyu alto mesayoqs.

service to this highest level of apu, these paqos are recognized as suyu alto mesayoqs.

There are two more stages of growth. After paqos become suyu alto mesayoqs, they might go on to reach the stage of the teqse paqo, or universal paqo. This is a paqo whose power can reach the entire world. Finally, there is the kuraq akulleq, which translates to something like the Elder Chewer of Coca or the Great Chewer of Coca. To my knowledge, at any one time there is one paqo who holds this position. Kuraq akulleq is a title conferred on an exceptionally wise and highly developed alto mesayoq through the consensus of a community. It is not something a paqo calls him- or herself. Rather, it is an honor bestowed by the community in recognition of that paqo’s expertise and experience and how he or she can serve that community.

Q: Who determines what kind of paqo someone is?

I am sure there are many ways to be called to the paqo path, but from what I have heard from the paqos I have interviewed or talked with (through translation), a paqo is called to be a particular type of paqo by an apu, another spirit being who serves as the representative of the apu, or by Taytanchis/God. When a person feels the call, he or she may go to an already established paqo, particularly an alto mesayoq, to discover if the call is real and, if so, what it means. The alto mesayoq may do a coca-leaf reading or consult with his or her misha, the spirit beings, or an apu to determine if this person’s call is to the path of pampa mesayoq or alto mesayoq. Sometimes, the person will intuitively know which type of paqo he or she is being called to serve as. That person has a choice to accept that call or not. For instance, as one paqo told me, when he consulted an established paqo about anomalous (and challenging) events that were happening in his life, the elder paqo told him he was being called to the path of the alto mesayoq. But this young man did not want the responsibility of being an alto mesayoq. If he was going to learn to be a paqo, he felt he would best fit into the role of a pampa mesayoq. And so that is what he trained to become.

Q: Should we call ourselves paqos? What kind of paqo are we training to become?

Although we might call ourselves paqos, what we mean by this is something different from what that title means in the Andes. For most us, we call ourselves paqos simply as a convenient way to indicate that we are learning or practicing the Andean sacred arts. But we are not literally paqos.

Paqo is a term rooted in the Andean culture. Thankfully, this is a culture that freely shares its tradition and practices. So, we are not in danger of cultural appropriation, for the paqos freely share the tradition. Today, they are almost always compensated for their time and expertise. However, payment does not negate the “ayni” (reciprocity) that truly drives their intent. They feel the energy practices are for everyone: we are all human beings and the goal of the work is to consciously evolve our humanness. However, we are at risk of cultural appropriation if we think of ourselves as either a pampa mesayoq or an alto mesayoq. These are not roles applicable to or recognized within our own cultures, and we risk misunderstanding what we are doing as practitioners of the Andean sacred arts if we think of ourselves as being either of those. An exception might be made if we spend time in the Andes apprenticing with a paqo and that teacher confers one of those titles on us. Still, if we come back to our communities, we no doubt will undertake that role in our own culture in  ways that are distinctly different from what it looks like in the Andes.

ways that are distinctly different from what it looks like in the Andes.

The bottom line is that we are not training to be paqos except in the most utilitarian sense of using the same techniques that Andean paqos do to foster our ayni and fertilize our personal development. Therefore, calling ourselves “paqos” is mostly just a convenient way to talk among ourselves and acknowledge we are learning and practicing Andean energy dynamics. We likely would not use the term outside of our common community of practitioners since it would be meaningless to anyone else.

Q: What are the duties and responsibilities of a paqo?

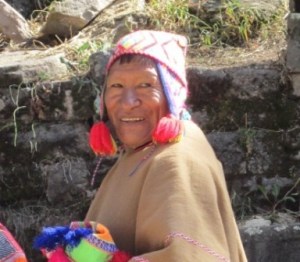

Paqos are first and foremost regular human beings, regular members of their communities. They are farmers, herders, weavers, husbands or wives, parents, friends, and neighbors. Their focus is on the duties and responsibilities that occupy daily life. No paqo whom I ever met is engaged full-time in his or her role as paqo. So, paqos are not spending most of the day communing with the spirit beings or performing rituals. They are going about their mundane daily lives until someone needs them to serve in their paqo capacity. What is that primary capacity? To serve their community.

Being a paqo means a person has knowledge and skills (and hopefully wisdom) that are above and beyond those of other community members. Although most Andeans understand and practice ayni and know how to make a despacho and so on, paqos are specially trained. When they are serving in their paqo capacity, they might be doing any number of things. While they may perform a ritual such as a despacho or undertake a healing, mostly they offer advice or solutions to people’s problems, sometimes gaining insight into the problem and the solution by throwing and reading the coca leaves. They may lead life-transition ceremonies such as the hair-cutting ceremony or some other coming-of-age ceremony,. They might lead a festival on a holy day or perform blessings for a wedding or death. Most of what they do is not “mystical” or “shamanic,” but practical. If I were to choose one primary responsibility that a paqo has it would be to foster social cohesion. That in turns helps ensure the well-being of all the members of the community. Don Benito Qoriwaman called the mountain spirits, the apus, the Runa Micheq, the shepherds of human beings. That, too, is the primary duty of an Andean paqo.